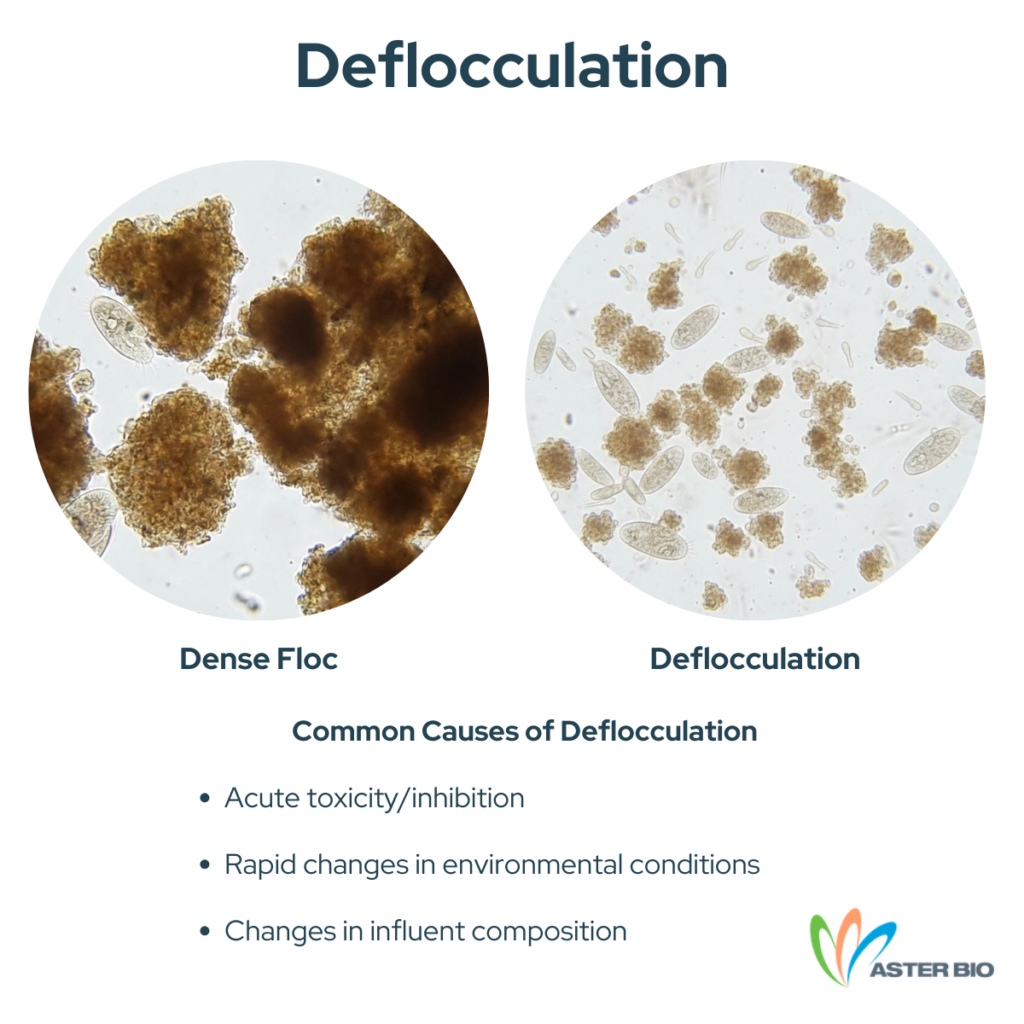

Deflocculation is one of those operational problems that can turn a perfectly healthy activated sludge system into a cloudy, turbid mess. Instead of forming tight, settleable flocs, biomass disperses into fine particles that slip through clarifiers, raise effluent TSS, and frustrate operators.

Even well‑run plants can experience deflocculation because it’s driven by subtle shifts in microbial physiology and wastewater chemistry. Understanding the root causes is the first step toward preventing it.

Sudden Deflocculation

Toxic or Inhibitory Shocks

Certain compounds disrupt the extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that hold flocs together. When EPS production drops or EPS is chemically damaged, flocs fall apart.

Common culprits include:

- Heavy metals (copper, zinc, nickel)

- Solvents and hydrocarbons

- High concentrations of surfactants

- Industrial cleaners and disinfectants

- Cyanides or phenolic compounds

These substances interfere with cell membranes and EPS synthesis, causing biomass to disperse even if the microbial community survives.

Sudden Changes in Wastewater Composition

Biological systems thrive on consistency. Rapid shifts in influent characteristics can destabilize floc structure.

Examples:

- Large swings in pH

- Temperature shocks

- Sudden increases in BOD or COD

- Rapid introduction of new industrial waste streams

Microbes need time to adjust their EPS production and community structure. When conditions change too quickly, flocs destabilize.

Gradual Deflocculation

Nutrient Deficiency (Especially Nitrogen or Phosphorus)

Microbes need balanced nutrients to build EPS. When carbon is high but nitrogen or phosphorus is low, bacteria shift into a “survival mode” and stop producing the sticky polymers that create floc structure.

Typical warning signs:

- High F/M ratio

- Rising effluent TSS despite normal MLSS

- Foaming or scum from dispersed biomass

A simple nutrient imbalance can mimic toxicity because the effect—loss of EPS—is the same.

Low Dissolved Oxygen (DO) or Anoxic Pockets

Oxygen stress changes microbial metabolism. Under low DO:

- EPS production decreases

- Filamentous bacteria may gain a competitive advantage

- Flocs become weak and fragile

Systems with poor mixing or overloaded aeration basins often see deflocculation during peak flows or warm weather.

Endogenous Respiration / Old Sludge

When sludge ages beyond its optimal range:

- Cells consume their own EPS for energy

- Flocs become loose and fragile

- Biomass disperses into the bulk liquid

This is common in systems with:

- Very long sludge ages

- Low loading periods

- Excessive wasting delays

Old sludge behaves like a starving organism—EPS is the first thing to go.

High Sodium, Potassium, or Other Monovalent Cations

Floc formation depends on cation bridging, where divalent ions like calcium and magnesium help bind EPS together. When monovalent ions dominate:

- Bridging weakens

- Flocs disperse

- Effluent turbidity increases

This is often seen in food processing, chemical manufacturing, and facilities with high brine loads.

Bringing It All Together

Deflocculation isn’t caused by a single factor—it’s the result of anything that disrupts EPS production, damages EPS, or destabilizes the microbial community. The key is to look for patterns:

- Did influent chemistry change?

- Did DO drop or aeration change?

- Is sludge age drifting?

- Are nutrients balanced?

- Any signs of toxicity?

A systematic review of operating data usually reveals the trigger.